Hosted by Jakob Muus, Director of Transporeon's Sustainability Tribe and joined by David Cebon, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Cambridge, Pieter Leonard, Chair of Efficient and Low Emission Assets and Energy at ALICE, and Thomas Fabian, Director Commercial Vehicles at the European Automobile Manufactures’ Association (ACEA), this special edition masterclass answered questions like: What can we expect from the electrification of fleets and when can we expect them? What else needs to be considered to reach net zero? How can we reduce CO2 emissions based on the knowledge derived from CO2 accounting and alternative fuel sources?

Rip Up the Golden Ticket Theory

03/21/2023 | 10 min

Takeaway 1: The Golden Ticket theory is a dud

The so-called ‘Golden Ticket’ theory claims that the transport industry can sit back, do nothing and relax in the pursuit of emissions reduction, because as every vehicle will soon be electric anyway, the problem will thus soon be solved.

The Masterclass experts were united: wrong.

Pieter Leonard, of Colruyt Group (a Belgium-based €10-billion p.a. retailer with over 700 stores and 250,000 km of transport journeys every day) and European logistics trade body ALICE, pointed out that electric vehicles on their own simply cannot solve the problem for two important reasons.

First, the costs are simply too prohibitive and require huge efficiency savings alongside the introduction of electric vehicles. Second, there is simply not the time available to us if we are to meet the 1.5° Paris Accord requirements on schedule.

No current graph – and all three panellists showed versions from different perspectives to demonstrate this – however optimistic, has the required target being hit without a major sea change in our vision and our execution. Yes, the vehicles are being tested and manufactured, but the fuel/energy question has not been fully answered, and the required infrastructure is neither in place nor, at current projections, likely to be.

Takeaway 2: Don’t focus on the shiny objects

Pieter Leonard expanded on this theme, pointing out that even if we electrify every traffic flow on the road today, we would still have to tackle the issue of systems inefficiencies, which currently make the transition unaffordable for logistics companies, retailers and shippers – indeed, the whole sector.

Alongside the transition to electric fleets, efficiency strategies must play a central role. In essence, that means ‘Avoid and Shift’ rather than buying shiny new objects. Use other modes where practical – maybe inland waterways might be appropriate in some relevant territories, for instance – share facilities and assets, avoid peaks, optimize loading to make processes more affordable. Colruyt has made gradual changes to its logistics flows, with the overall aim of cutting the total number of movements.

That applies to incoming flows, too. Colruyt is applying its experience in the field of ‘avoid and shift’ to help suppliers and partners to make this transition affordable.

“Make your existing transport flows as efficient as possible before you prioritize electrification,” he recommends.

Takeaway 3: TCO will be the game-changer

Thomas Fabian explained why the drive to Net Zero via electrification is simply not going to happen naturally. While we are seeing slow but steady improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency of roughly 1% p.a., the reduction is cancelled out by huge increases in transport demand, which is up by 25% over the past 20 years.

Total cost of ownership (TCO) is therefore going to be the game-changer. As soon as it becomes more attractive to operate more cost-effectively with a non-emitting vehicle, any business still operating an emission-unfriendly vehicle is going to lose money. This is a scenario the industry needs to create.

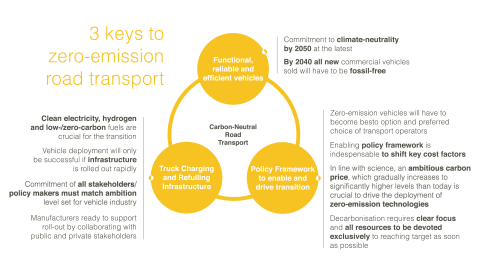

To decarbonize effectively, three factors need to be in place:

- The vehicles have to be available, and clearly the industry is already working hard on that.

- Fuel, energy and infrastructure also have an essential role to play, because without the ability to charge and recharge or refuel at will, no transport operator will be able to invest in a vehicle, no matter how strong the TCO on that vehicle.

- TCO: zero-emission vehicles have to become the best option and the preferred choice of transport operators. Again, this won’t happen by itself.; iIt needs an ambitious carbon pricing framework, which can consist of different policy elements, but which needs to push operators away from conventionally fuelled and towards zero-emission vehicles.

Decarbonisation will happen in earnest once these factors are in place.

Takeaway 4: Vehicles will not be the bottleneck

We need to be fossil-free by 2040, but there is a corridor of uncertainty around delivery date and our ability to meet it. The speed of transition will depend on the enabling factors of infrastructure and TCO parity.

Robust carbon pricing is going to be key, while the charging and refuelling infrastructure for HDVs requires a very different set of criteria to that needed for passenger cars. Locations, space requirements and minimum power output levels are all essential considerations.

The numbers are sobering. Current HDV targets require at least 230,000 battery-electric vehicles (BEV) on the road by 2030, with 180,000 long-haul capable, requiring Megawatt Charging System (MCS) capability.

By 2030, 40,000-50,000 truck suitable, publicly accessible chargers will be needed. Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) targets therefore reveal a significant infrastructure gap in this area until at least 2030.

In the event that Net Zero targets require an even higher BEV/FCEV share, that of course means an even higher infrastructure demand.

In short, it’s about a lot more than ‘just’ CO2 standards: vehicles, cost parity, fuel/energy, and infrastructure need to be up to speed.

Takeaway 5: Hydrogen – yes, no, maybe...

For Pieter Leonard and Thomas Fabian, hydrogen combustion and Fuel Cell technology (FCEV) have a role to play as the industry looks for alternative solutions to fossil fuels. Yes, the technology is expensive, but they can see where it might plug some holes as grid capacity is stretched, particularly given the speed with which the industry needs to act.

Not so, says David Cebon. For him, hydrogen is not only ruinously expensive, it also fails as a low-emissions solution because it requires high carbon emissions in the manufacturing process. For Professor Cebon, we need to look at charging infrastructure first and foremost.

Takeaway 6: It’s about the infrastructure, not the vehicles

There are two ways to improve efficiencies in the road freight industry – either via vehicle or via road freight operations. For David Cebon, the latter is where the real wins – and therefore the future for long-haul road freight – will emerge.

While there are technologies for reducing consumption, with many easy to adopt, the problem is that the resulting efficiencies are low. They include driver training, improved transmissions, vehicle aerodynamics, better tyres, tyre pressures; smoother roads. With CNG/LNG facing infrastructure challenges, biogas availability limited, hydrogen a challenge (for the reasons above), the only serious wide-use energy on the table for long-haul is electrification.

We are already seeing the rapid electrification of vehicular delivery transport in urban areas, so we know the technology can work. The challenge is to build the technologies and supply chains for the much higher capacity electric vehicles needed for long-haul.

With data-based evidence from thousands of long-haul HDV journeys in the UK, the Centre for Sustainable Road Freight conceived an Electric Roads System (ERS) for main trunk routes, with high-capacity fast chargers situated in remoter areas unlikely to receive heavy traffic. On the main trunk routes, HDVs would be charged by the electric system within the road itself (concepts currently in testing include both overhead pantograph-wire systems and induction systems by which the charging system is embedded in the road surface).

Without such a charging system, HDVs would require enormous battery sizes, far bigger than anything currently contemplated by OEMs. However, with the appropriate road charging system in place, Professor Cebon’s team established that battery sizes can be reduced dramatically to levels much more in line with those currently in production and being proposed. Battery size is no longer a hurdle to both efficiency and lower costs in these circumstances.

Projected TCO figures showed a strong advantage for an ERS model over both fossil-fuel and electric (without ERS) futures. Indeed, one where instead of subsidising to make TCO affordable, governments might have the scope for taxation and revenue-raising opportunities.

Highlights from the Q&A

THOMAS: Rail will have to play an important role but it's not going to reduce the need to decarbonise road, so in that respect it has a rather limited potential as (1) the structure of freight has changed and continues to change, favouring more decentralised and flexible modes of transport, and (2) the current state of railways is considered insufficient and will require massive investments (which will take time to materialise). Besides, the regulatory framework is complex.

PIETER: Intermodal transport is a good solution for decarbonisation. We only must keep in mind that it does not suit all transport flows. As mentioned in my presentation we should first look to optimise transport (reduce the demand), then look for the best mode (and intermodal would be better than road) and only then to electric road transport. As in most cases it’s important to look for the mode best suited to meet the criteria of the freight demand.

THOMAS: Vehicle manufacturers have clear SBTI targets and aim to reduce or decarbonise their scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. Logistics provides and transport operators in all modes should (or do) have similar ambitions and targets and reduce their carbon footprints. Zero emission, in that sense, refers to the use phase of the vehicles with zero local carbon emissions.

PIETER: All companies in the value chain have to take their responsibilities and we (companies and consumers) have to challenge them on that. The detailed answer I would leave up to the OEMs.

THOMAS: We already have a stringent regulatory framework in Europe which requires OEMs to reduce the average emissions of their new vehicle fleet by 15% (by 2025) and 30% (by 2030), compared to a 2019/2020 baseline. The European Commission has recently proposed revised targets of 45% (2030), 65% (2035) and 90% (2040), but already the current regulation requires well more than 300,000 zero-emission vehicles in operation by 2030 (180,000 of which will have to be heavy-duty long-haul vehicles).

Currently, there is close to no charging or refuelling infrastructure in place to support this fleet, let alone an even bigger fleet, should the CO2 targets be increased beyond the current level. Zero-emission vehicles will not be the bottleneck in the transition to climate neutrality. As of now, the lack of infrastructure remains a major bottleneck as are TCO which favour the operation of conventionally powered vehicles.

THOMAS: Here are some estimates and calculations for BEV trucks: https://www.acea.auto/files/Research-Whitepaper-A-European-EV-Charging-Infrastructure-Masterplan.pdf

THOMAS: Hydrogen will play a key role in decarbonising heavy-duty road transport, especially in view of the persistent lack of charging infrastructure.

PIETER: If we have chosen the road of electrification (we have optimised and chosen the right mode) than we must look into a good energy carrier. Both Batteries and Hydrogen have their pros and cons, but it is essential that we use green energy to charge the batteries and produce the hydrogen. Using grey electricity or hydrogen will not give us a zero-emission value chain.

Great question. I would argue that we should all strive to reach it but should set equally ambitious targets for all players in the value chain. Currently, only vehicle manufacturers face non-compliance penalties should they not be able to reach their CO2 reduction targets. No penalties of a similar level would apply to other stakeholders in the transport and logistics value chain, even those sectors that are crucial for providing key enabling conditions, such as the charging and refuelling infrastructure.

PIETER: I'm sure we can reach it. Maybe 10 years is a bit short. We all have to push our governments.

DAVID: I didn't have HVO on my graph, but I had biogas, which can also be made from waste biomass. The message is similar for the two. They both give 70-80% emissions reduction, but both have very high barriers to widespread adoption, because there is not nearly enough biofuel available to power all heavy road vehicles.

PIETER: Logistics is fully managed in-house, and we orchestrate transport (we hire drivers and trucks but decide on their tasks). The transport eco system will change in the next 10-20 years. We have to make sure that our service providers can make this change happen with us. We invite them on a regular base to explore in partnership what would be needed to tackle the challenges of the future.

PIETER: A good network design is essential to reduce freight demand, so we study it from time to time and make adjustments where possible to create value in the entire value chain.

Final Thoughts:

- The Golden Ticket theory should be dismissed. Now.

- The transport industry is not going to meet any of the required Net Zero targets on current projections.

- It is not enough to talk about putting more electric HDVs on the roads - we need to make dramatic efficiency savings too. And the time to make those savings is now.

- Real mindset change will only happen when the TCO of sustainable energy models beats that of fossil-fuel models. And that means robust carbon pricing.

- The future is electric, but not exclusively – at least, not yet. Hydrogen may have a role to play but it expensive and its manufacture is not low-emission. The jury is out.

- Infrastructure, infrastructure, infrastructure. Only by introducing cost-effective, time-efficient power-charging systems appropriate to the demands of sleek logistics will we make that step change. Electric Road Systems (ERS) can square the circle of battery cost and size efficiency versus HDV logistics demands. But pressing the ‘Go’ button on ERS will be the biggest decision of all.

Carbon Intelligence Mastermind

Look out for the next activities part of our Carbon Intelligence Mastermind Community. Join the community now so you won’t miss any meetups and masterclasses.